Writing as Thinking

And AI as Constraint Satisfaction Problem Solver

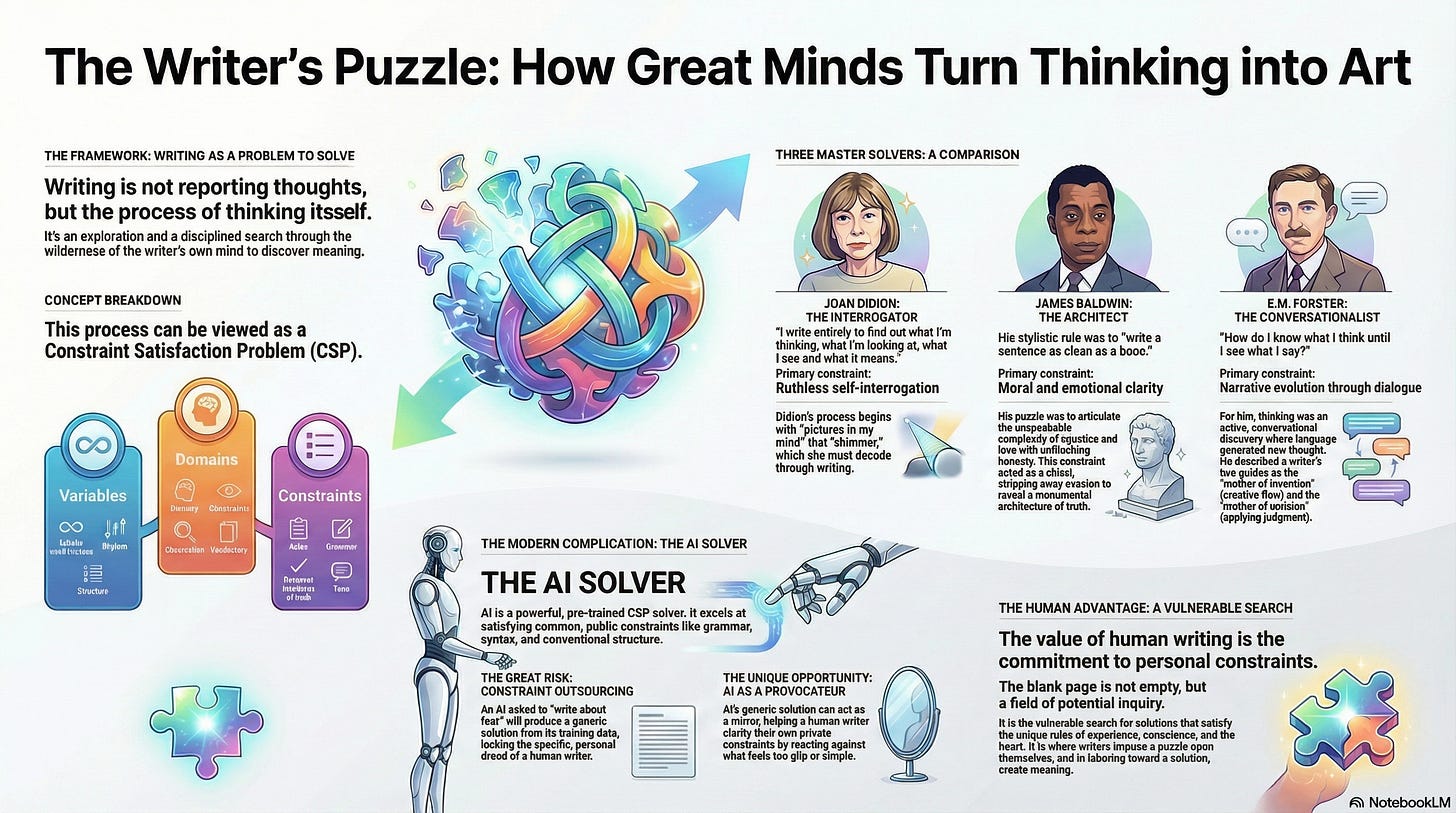

We often imagine a writer’s mind as a well of inspiration or a generator of perfect thoughts. The reality is far more dynamic. Writing is not merely the reporting of pre-formed ideas, but the very process by which thinking happens—a disciplined search through the wilderness of our own minds. As Joan Didion famously confessed,

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.”

Writing, in its purest form, is exploration.

This creative struggle can be understood as solving a generalized, non-numeric Constraint Satisfaction Problem (CSP), where the goal is to find a configuration—a sentence, a paragraph, an argument—that satisfies a complex web of rules. A writer navigates:

Variables: The infinite choices of word, rhythm, and structure.

Domains: The universe of memory, observation, and vocabulary.

Constraints: The rules, from hard grammar to soft, personal standards of truth and tone.

A writer’s unique voice emerges from the specific, often profound, constraints they choose to prioritize and how they solve for them.

The Interrogator, the Architect, and the Conversationalist

Three writers exemplify this process through distinct, yet connected, approaches to their personal constraint puzzles.

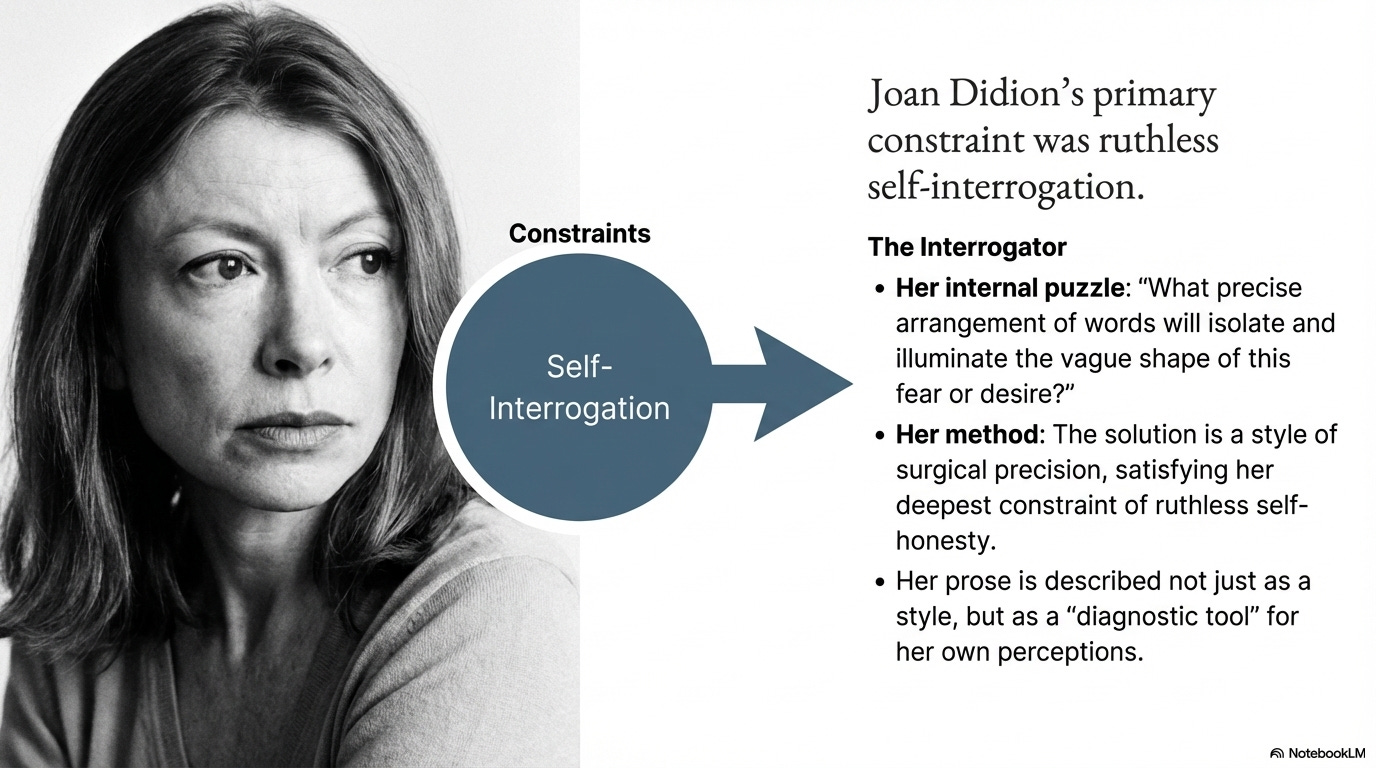

Joan Didion: The Interrogator. For Didion, the supreme constraint is interrogation of the self. Her writing is a forensic audit of her own perceptions and anxieties. The puzzle is internal: What precise arrangement of words will isolate and illuminate the vague shape of this fear or desire? The solution is a style of surgical precision, a prose so clean it becomes a diagnostic tool, satisfying her deepest constraint of ruthless self-honesty.

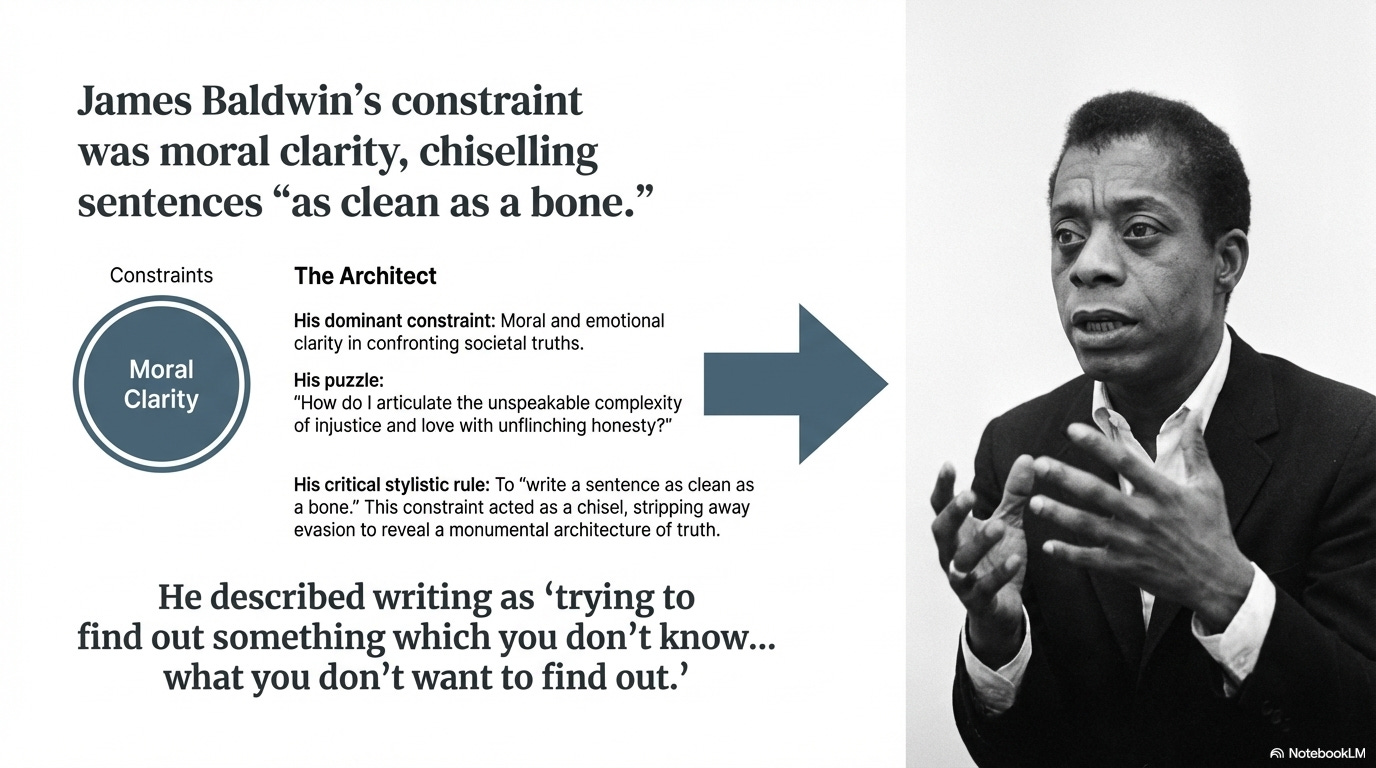

James Baldwin: The Architect. For Baldwin, the dominant constraint was moral and emotional clarity in confronting societal truths. His puzzle was: How do I articulate the unspeakable complexity of injustice and love with unflinching honesty? He described writing as “trying to find out something which you don’t know... what you don’t want to find out.” To solve this, he imposed a critical stylistic rule: to “write a sentence as clean as a bone.” This constraint of clean-bone clarity acted as a chisel, stripping away evasion to reveal a monumental architecture of truth, where every word carries moral weight.

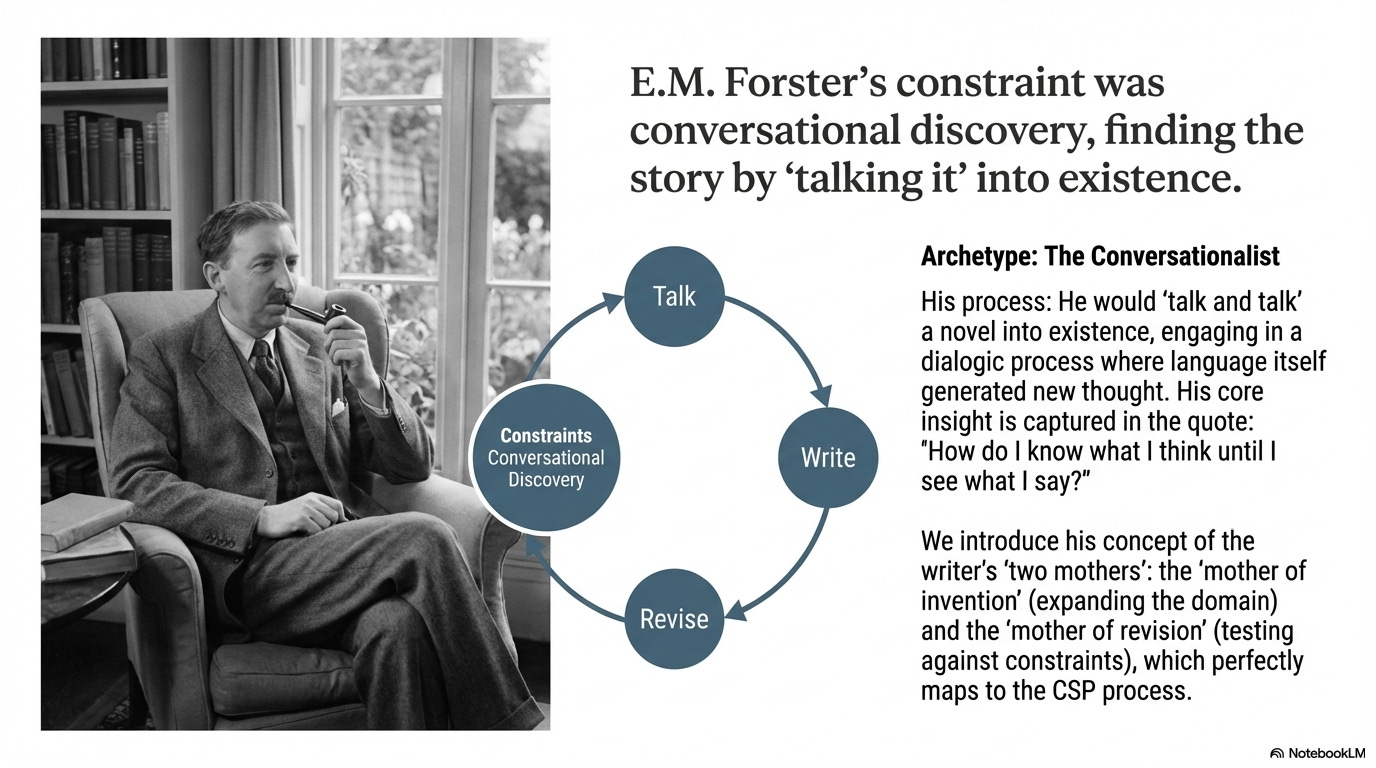

E.M. Forster: The Conversationalist. Forster introduces a vital, social dimension to the CSP. He famously said, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” For him, thinking was not a silent, internal event but an active, almost conversational discovery. He would “talk and talk” a novel into existence, engaging in a dialogic process where language itself generated new thought. His constraint was narrative evolution through dialogue, both internal and with characters. He saw the final plot not as a pre-planned blueprint, but as “the evolution of feeling and thought in the life of the characters,” a solution arrived at through spoken and written trial. Furthermore, he acknowledged the writer’s dual role, guided by what he called “two mothers”: the “mother of invention” who encourages boundless creative flow (expanding the domain), and the “mother of revision” who applies critical judgment (testing against constraints). His process is the CSP in live action: generating possibilities through talk, then evaluating and refining them.

Orchestrating Intelligence: The Human as System Architect

The modern writer’s condition is newly complicated by the presence of artificial intelligence. To understand this collaboration—and its pitfalls—we must move beyond vague warnings. We can formalize the dynamic by viewing the writer not just as a thinker, but as a System Architect, and the AI as a High-Speed Heuristic Solver. This framework transforms writing from a solitary CSP into a managed collaboration where the primary task is orchestrating intelligent friction.

In this partnership, the components of the Writing CSP are shared, but sovereignty over them is carefully partitioned:

Variables & Domains: The AI provides breadth and velocity, flooding the domain with plausible candidate solutions from its vast statistical library. The human provides depth and idiosyncrasy, drawing from the “Personal Domain” of lived experience, memory, and unique sensibility.

Constraints: These stratify into a crucial hierarchy:

Hard Constraints (Grammar, Syntax): Largely delegated to the AI solver.

Soft Constraints (Tone, Pace): A hybrid negotiation.

Higher-Order Constraints (Truth, “Soul”): The exclusive, sovereign domain of the human Architect. These are the epistemic questions: Does this align with my felt experience? Does it have the necessary moral weight? Does it bear my unique mark?

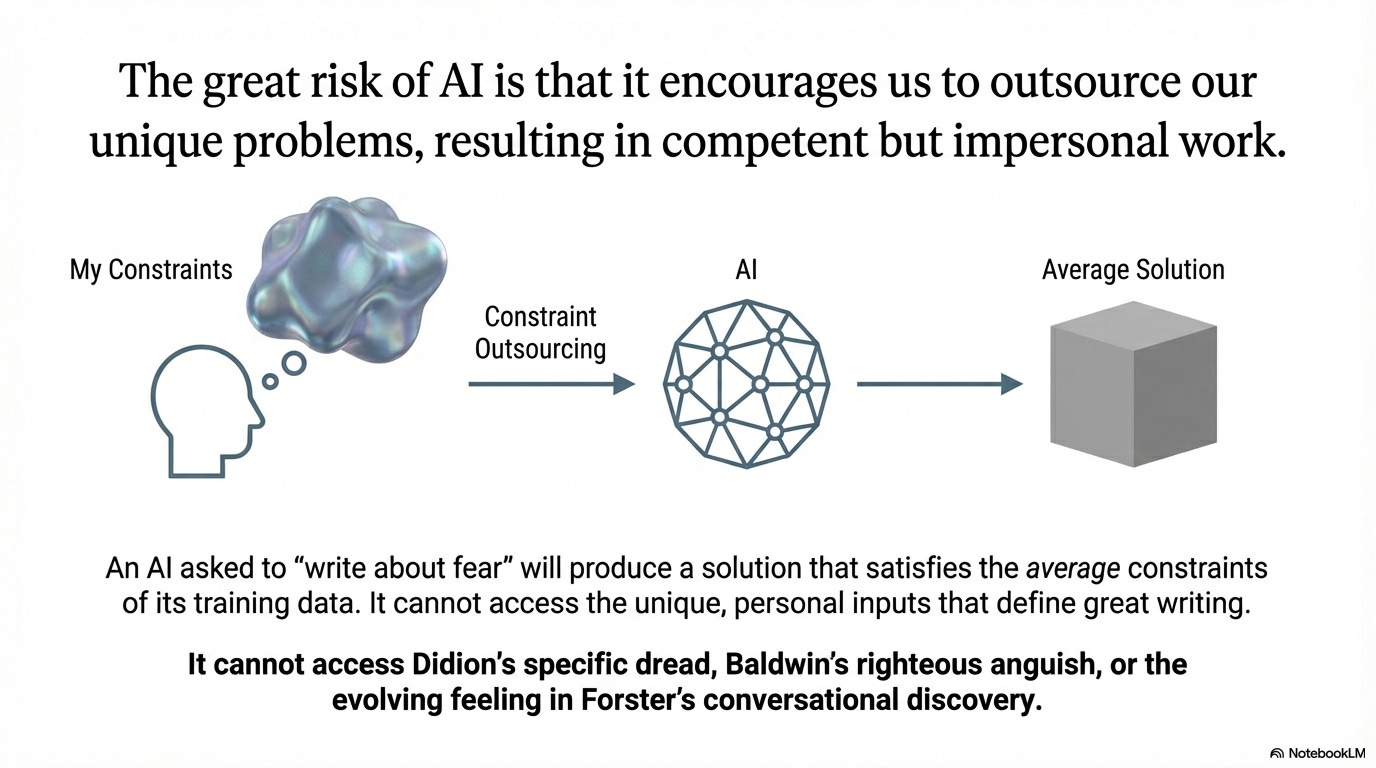

The central risk is not that AI will write poorly, but that it will solve the wrong problem too efficiently. If it satisfies only the average, statistical constraints of its training data, the outcome is generic “production,” not thinking. The writer’s role, therefore, shifts from mere generator to Architect of a “Thinking Filter”—a series of protocols designed to use the AI’s speed to force deeper human definition.

Protocol 1: Divergence (Expanding the Domain to Force Conflict).

The Architect commands the Solver to generate a surplus of options: “Give me ten metaphors for memory from geology, liturgy, and broken machinery.” The goal is not to find the “right” answer, but to provoke a reaction. The thinking occurs in the negative space: Why is this metaphor glib? Why does that one feel alien? By identifying why an AI’s suggestion is “soulless,” you are forced to define what the “soul” of your own idea actually is. The friction here is generative.

Protocol 2: Constraint Injection (Asserting the Personal).

Here, the Architect manually injects a “non-average,” deeply personal constraint that breaks the AI’s statistical mold: “Rephrase this analysis of societal pressure so the rhythm mimics the sound of a distant subway train.” This forces a reconciliation between abstract concept and specific, sensory experience. The AI struggles to solve for this eccentric rule, and in directing its struggle, the writer must articulate and refine a constraint that exists nowhere but in their own sensibility.

Protocol 3: Backtracking (Resolving Gaps through Rethinking).

When a passage feels “hollow” or too easily resolved, the Architect triggers a backtrack. The AI is tasked as a Constraint Auditor, asked to find the logical or emotional weakest link. The critical rule is this: if a gap is found, the AI does not fix it. The Architect must return to their internal model—their core premise or feeling—and rethink it. This protocol ensures that logical repair stems from a deeper epistemic shift, not a surface-level patch.

In this framework, Joan Didion, James Baldwin, and E.M. Forster appear as instinctive, supreme Architects of their own internal systems. Didion incessantly injected the constraint of personal truth; Baldwin imposed the constraint of clean-bone moral clarity; Forster operated the Divergence Protocol through endless conversation. They created their own friction.

The contemporary writer must now learn to consciously architect a hybrid system. The blank page is now also a console. Thinking remains what it has always been: the often-uncomfortable process of discovering which constraints are truly worth satisfying. The AI, properly orchestrated, does not simplify this quest. It can deepen it, by turning the solitary CSP into a dialogue where our highest-order constraints—the search for what we see, what we fear, and what it means—are clarified under a new, accelerated pressure.

Synthesis: The Unified Search

While their primary constraints differ—Didion’s self-interrogation, Baldwin’s moral truth, Forster’s evolving conversation—their processes unite in the CSP model. Didion uses the page as a lab, Baldwin as a chisel’s block, and Forster as a conversational partner. Yet for all, “thinking” is the iterative act of testing language against their deepest, self-imposed standards

In a world where AI can satisfy surface-level constraints, the writer’s essential task is to dive deeper. The value lies in the commitment to the vulnerable search for solutions that satisfy the most personal constraints: the constraints of experience, conscience, and an unruly, seeking heart.

The blank page, therefore, is not emptiness but a field of potential inquiry. It is where we, like Forster, discover what we think by seeing what we say; where, like Baldwin, we chisel clean bones of truth; and where, like Didion, we map the contours of our inner world. It is where the human act of imposing a puzzle upon oneself, and laboring toward its solution, becomes the very act of creating meaning.

References

Didion, J. (1976). Why I Write.

Baldwin, J. (1984). The Creative Process

Forster, E.M. Aspects of the Novel and related lectures/notes