Why the "spiked virus" is a better metaphor for ideas than "connecting the dots"

A Follow-Up to “Seeing X as Y”

This article is a continuation of the ideas explored in the two earlier pieces “Seeing X as Y” and its follow-up, “Revisiting Seeing X as Y.” In those essays, we examined how human thought doesn’t just connect ideas—it transforms them. We don’t merely observe facts; we interpret them. We don’t just compare things—we reframe them. And at the heart of creativity lies this powerful cognitive act: seeing one thing as another.

From Tesla selling a mission instead of cars, to Word2Vec turning words into vectors, to Fourier revealing that noise is made of pure waves—these aren't random associations. They are profound shifts in perception. As Ulam urged: it’s the word “as” that needs to be formalized. Because "seeing X as Y" is not decoration. It's discovery.

But here’s a question those articles left open:

Why do some "X as Y" connections work brilliantly… while others collapse like bad glue?

The answer isn’t just about cleverness. It’s about compatibility.

And to understand compatibility between ideas, we need a new metaphor—one far more accurate than “connecting the dots.”

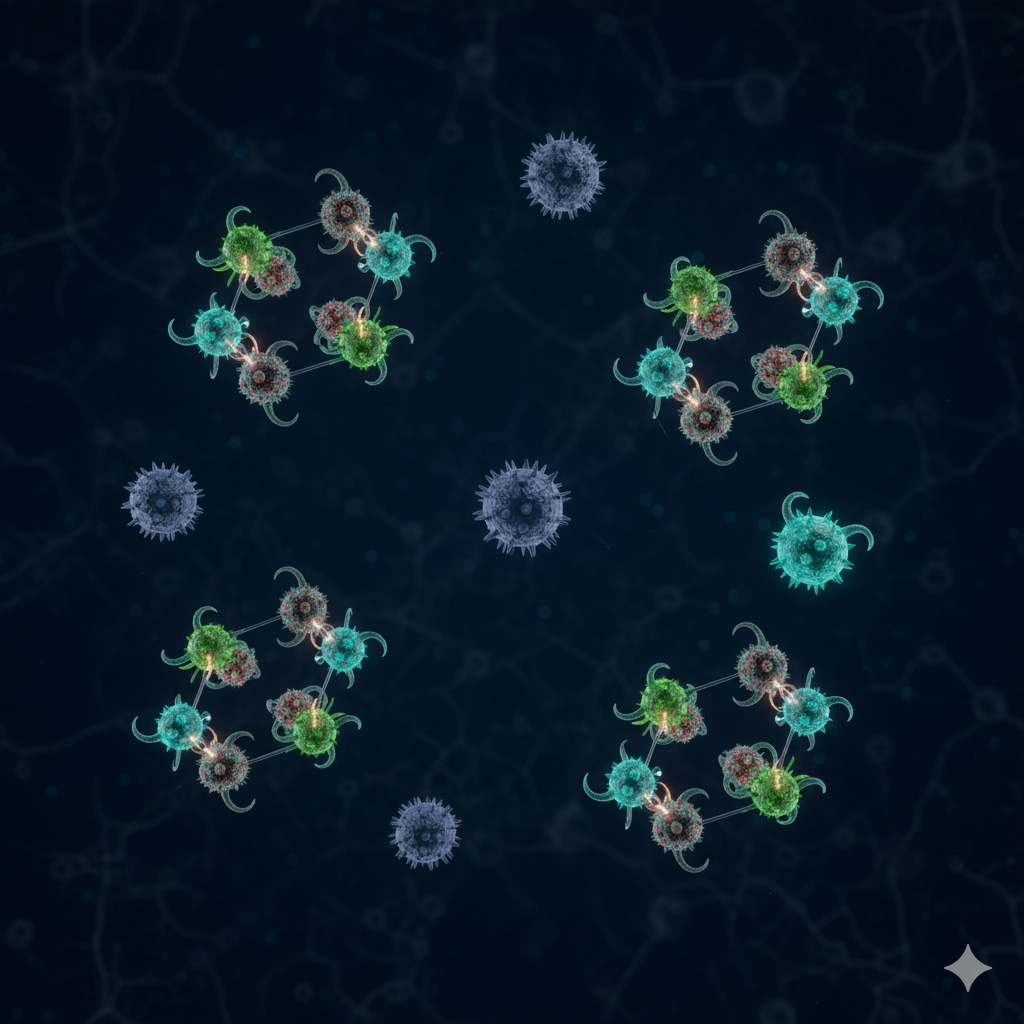

We need to think of ideas not as inert points, but as spiked viruses.

Yes—viruses.

Not because they’re dangerous (though some ideas certainly are), but because, like real viruses, ideas have structures that determine whom they can infect, where they can go, and what they can transform.

Let’s unpack that.

Why Dots Don’t Stick — And Why That Matters

We love the image of genius as someone who “connects the dots.” Steve Jobs did it. Einstein did it. You can too!

But here’s the problem: dots don’t resist connection.

You can draw a line from any dot to any other. No pushback. No failure. Just smooth, frictionless lines.

Real thinking isn’t like that.

Try connecting "a startup" to "a rocket." Sounds good, right? Both go up. Both need fuel. Investors love the pitch.

Now try using that analogy to solve a real problem—say, team conflict or product design. Suddenly, the metaphor falls apart. Rockets don’t negotiate. Startups do.

The connection looked solid—until you tried to use it.

That’s because real ideas aren’t passive dots. They’re active, structured entities with internal logic, emotional weight, assumptions, and boundaries. And these features act like spikes—proteins on a virus’s surface that only latch onto specific cell receptors.

Just as a coronavirus spike binds to an ACE2 receptor in your lungs, an idea only bonds to another when their cognitive spikes align.

So what exactly are these “spikes”?

Let’s break them down.

What Are Idea Spikes? (And Why Your Brain Is a Biodiversity Lab)

Imagine every idea you hold—like “justice,” “growth,” or “love”—is not a flat label, but a 3D object covered in specialized hooks, sensors, and docking ports.

These are its spikes: the hidden dimensions that determine whether—and how—it can combine with other ideas.

Here are the main types:

🔹 1. Semantic Spikes – The Meaning Anchors

Every word carries more than dictionary definition. It brings baggage: connotations, cultural history, ambiguity.

Example: “Freedom”

In politics: freedom from tyranny

In psychology: freedom to choose

In economics: free markets

These are different semantic spikes. Try plugging “freedom” into a discussion about AI ethics—you’ll get very different results depending on which spike shows up.

🔹 2. Structural Spikes – The Logic Connectors

This is about how parts relate: cause-effect, hierarchy, feedback loops, symmetry.

Example: Seeing a city as an organism

Roads = blood vessels

Power grid = nervous system

Waste management = kidneys

This works because both systems share feedback mechanisms, distributed networks, and emergent behavior—matching structural spikes.

But if you tried to see a poem as a city? Few structural hooks match. A stanza isn’t a district. Rhyme scheme isn’t zoning law.

It might inspire art—but won’t help urban planning.

🔹 3. Emotional Spikes – The Feeling Hooks

Ideas carry mood. Some spark hope. Others trigger fear, nostalgia, or awe.

Example: “Climate change”

Seen through data: analytical spike

Seen as a child’s future: emotional spike (urgency, grief)

When Greta Thunberg said, “Our house is on fire,” she didn’t offer new data. She switched emotional spikes—and ignited global action.

Same fact. New binding potential.

🔹 4. Ethical Spikes – The Moral Velcro

Some connections feel wrong, even if logically sound.

Example: Seeing employees as “human capital”

Matches economic models (structural spike ✅)

But erases dignity, agency, care (ethical spike ❌)

We reject this not because it’s false, but because its spike violates deeper values.

Like a virus blocked by the immune system, the mind says: “You may fit, but you’re not welcome.”

🔹 5. Temporal & Contextual Spikes – The Situational Fit

An idea that works in one era or culture fails in another.

Example: “Democracy as majority rule”

Fits 18th-century republicanism

Clashes with modern concerns about minority rights, misinformation, polarization

The spike hasn’t changed—but the host environment has.

So Why “Spiked Viruses”? A Biological Analogy That Works

You might wonder: why use such a dramatic metaphor?

Because biology gives us the clearest model of selective binding.

A virus doesn’t invade every cell. Only those with the right receptor.

Once attached, it doesn’t just sit there. It reprograms the host. It changes what the cell does, what it produces, even what it is.

That’s exactly what happens when a powerful idea takes hold.

Think of CRISPR again:

Scientists saw bacterial immune memory (odd DNA repeats)

Not as junk, but as a programmable gene editor

That’s a spike alignment: molecular recognition + precision cutting + heritability

One paper. One insight. And suddenly, medicine, agriculture, ethics—all reprogrammed.

The idea didn’t just connect. It infected and transformed.

Or consider Gandhi’s nonviolence:

He saw oppression not as a call to arms (the expected military spike)

But as a stage for moral theater (ethical + performative spike)

His method didn’t overpower the British army. It redefined victory.

The British had all the guns. But Gandhi had the better idea spike.

When Spikes Misfire: The Dark Side of Bad Bonds

Not all connections are healthy.

Just as some viruses hijack cells for destruction, some “X as Y” moves corrupt thinking.

Examples:

“Refugees as threats”

Semantic spike: danger

Emotional spike: fear

Structural spike: zero-sum competition

Result: policies that harm innocent people

→ A strong bond, but ethically toxic“Markets as perfectly rational systems”

Structural spike: equilibrium models

But ignores behavioral biases (emotional spike mismatch)

→ Helped cause the 2008 financial crash

These aren’t failures of imagination. They’re successes of misaligned spikes—connections that feel solid but lead us astray.

Which means we need more than creativity.

We need spike literacy.

🔄Category Theory: The Mathematics of "Seeing As"

This brings us to one of the most powerful tools for understanding idea-spikes at a deep level: category theory, a branch of mathematics that doesn’t focus on what things are, but on how they relate. In category theory, objects (like numbers, shapes, or data structures) matter less than the morphisms—the transformations between them. What counts is not identity, but interconnection.

Why is this revolutionary for “seeing X as Y”? Because it allows us to say, with precision, when two seemingly different domains are “the same in spirit.” For example:

Solving an equation in algebra

Tracing a path in topology

Optimizing a network in computer science

These might look unrelated. But if their transformation patterns match—if their spikes align—category theory shows they share a common structure. Mathematicians call this a functor: a mapping that preserves relationships across domains.

André Weil once dreamed of a “Rosetta Stone” linking number theory, geometry, and finite fields—precisely the kind of cross-domain insight that emerges when spikes dock correctly. Today, category theory is helping realize that vision, revealing hidden bridges between areas of math once thought isolated.

In cognitive terms? Category theory is the mathematics of "seeing as."

It formalizes Ulam’s call to “mathematize the ‘as.’”

It explains why some analogies generate new truths while others fizzle: because real insight isn’t about labels—it’s about lawful correspondences.

So when Airbnb sees lodging as belonging, or when Fourier sees noise as harmony, they’re doing something akin to a categorical functor: preserving the essential dynamics while transforming the surface form.

To build more resilient, creative minds—and machines—we don’t just need better metaphors.

We need a calculus of perspective, a grammar of transformation.

And category theory may be its first true language.

🔗 Key Reference: Eugenia Cheng, The Joy of Abstraction (2023);

Cultivating Spike Awareness: How to Think Like an Immunologist

To navigate the ecosystem of ideas, we must become cognitive immunologists—able to detect which ideas are generative, which are parasitic, and which simply don’t belong.

Ask these questions before accepting a “seeing X as Y” move:

What kind of spike is driving this?

Is it emotional? Structural? Ethical? All of the above?

Does it transfer function—or just flavor?

Can I do something new with this idea? Or is it just poetic?Where does it break?

Test edge cases. If I treat a school as a factory, what gets broken? Joy? Curiosity? Equity?Who benefits from this connection?

Follow the power. Does this reframing serve truth—or control?Can it evolve?

Good idea-spikes allow mutation. Bad ones demand dogma.

Final Thought: The Immune System of the Mind

Your brain is not a library. It’s an ecosystem.

Ideas flow in constantly—through books, conversations, algorithms, dreams.

Most vanish. Some stick.

The ones that stick aren’t always the truest. Often, they’re the ones whose spikes fit best—even if they’re misleading, comforting, or addictive.

To think clearly in the 21st century, we must go beyond “thinking outside the box.”

We must learn to see the spikes.

Because the most dangerous ideas aren’t the ones we reject.

They’re the ones that dock so smoothly we never notice they’ve rewritten our code.

And the most transformative ideas?

They often arrive looking foreign—awkward, unstable—until one day, their spike finds the right receptor…

And everything changes.

Further Reading & Inspiration

Mikolov et al., Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space (2013)

This seminal paper introduces Word2Vec, a neural network model that transforms words into high-dimensional vectors. It shows that semantic relationships (like gender or tense) can be captured as mathematical operations (e.g., king – man + woman ≈ queen), illustrating how "seeing words as vectors" enables machines to perform analogical reasoning.

James Gleick, The Information (2011)

A sweeping narrative on the history and impact of information theory. The book explores how ideas—from language to DNA to quantum physics—are encoded, transmitted, and transformed. It highlights the Fourier transform and other tools as foundational to turning complex phenomena into manageable information, showing deep connections between science, technology, and thought.

Walter Isaacson, The Code Breaker (2021)

This biography centers on Jennifer Doudna and the development of CRISPR gene-editing technology. It illustrates how scientific breakthroughs arise from "seeing X as Y"—in this case, viewing bacterial immune memory as a programmable tool for editing life. The book also examines the ethical dimensions of such powerful cognitive and technological reframings.

Eugenia Cheng, The Joy of Abstraction (2023)

A gentle introduction to category theory, a branch of mathematics that studies structures and relationships across different domains. Cheng shows how abstraction allows us to see deep similarities between seemingly unrelated fields—precisely the kind of "seeing X as Y" that reveals unifying principles in math and beyond.

Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1979)

A Pulitzer Prize-winning exploration of consciousness, creativity, and meaning through the lens of mathematics, art, and music. Hofstadter argues that analogy and self-reference are at the heart of thinking. His work deeply inspired the idea that cognition is not logical deduction but a fluid process of seeing one thing as another.

George Lakoff & Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (1980)

This groundbreaking book argues that metaphor is not just poetic language, but fundamental to thought itself. We understand abstract concepts (time, emotion, politics) through concrete metaphors (time is money, anger is heat). The book shows how "seeing X as Y" structures our everyday reasoning, often without us realizing it.

🧠 Remember:

You're not just thinking with ideas.

You’re navigating a vast, invisible forest of spiked entities —

waiting for the moment when one finally clicks into place.

But make sure it’s building immunity… not infection.