They Do Not Knock; They Dock

How the “Spiked Virus” Framework Transforms Creative Thinking

(Note: This essay acts as a Folgezettel within the “Seeing X as Y” trilogy, expanding on why the “spiked virus” is a superior metaphor for ideation than “connecting the dots.”)

The Geometry of Insight

The most dangerous ideas arrive not as arguments, but as geometries. They do not knock; they dock.

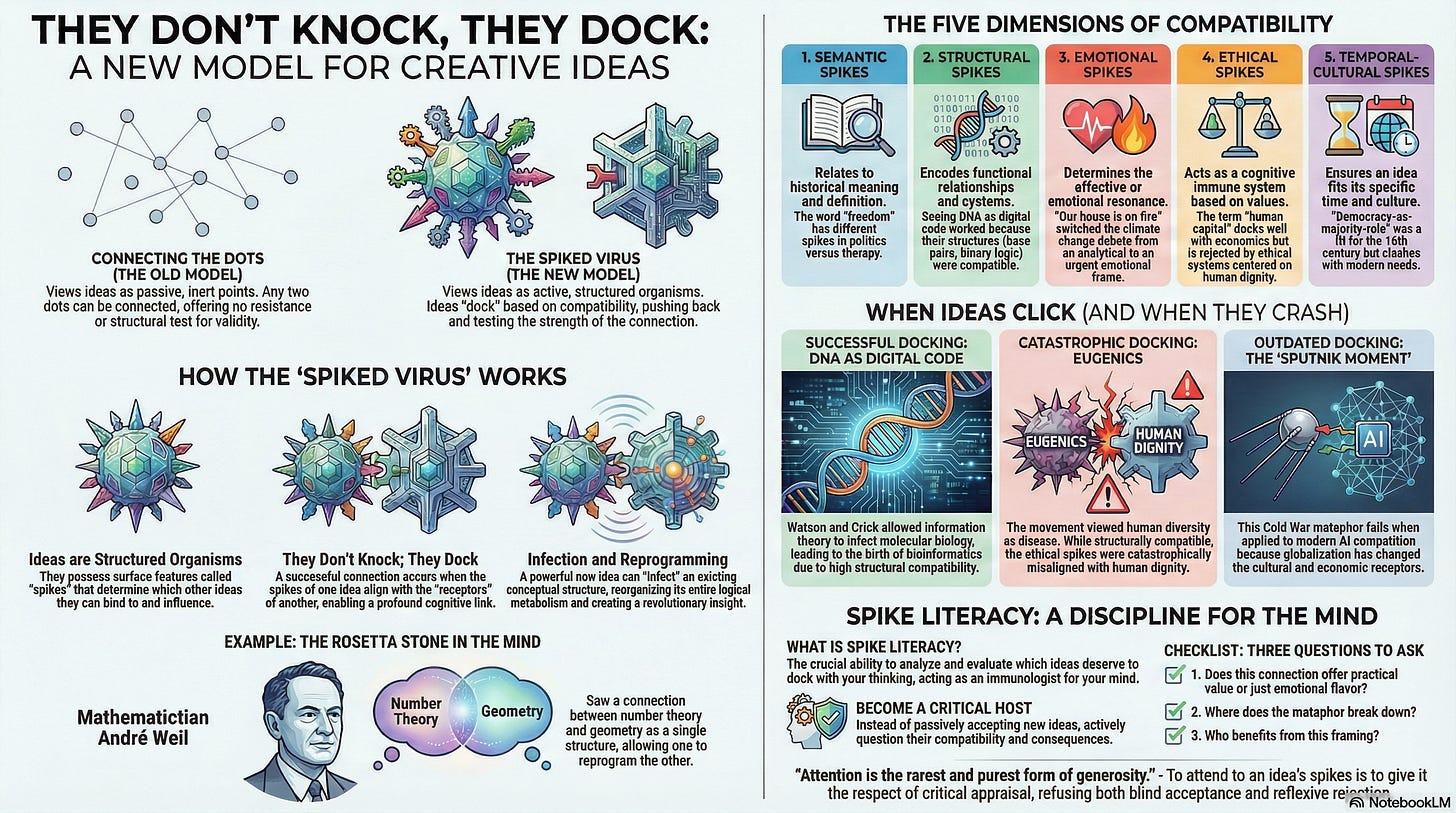

When the French mathematician André Weil was confined in a military prison during World War II, he wrote to his sister, Simone, claiming he had discovered a “Rosetta Stone” connecting number theory, algebraic geometry, and finite fields. Weil was not making a metaphor. He was describing a physical reality within his mind: an act of cognitive recombination so profound that it reorganized mathematics itself. Weil had not merely connected dots. He had allowed one conceptual structure—a system of prime numbers—to infect another, remapping its entire logical metabolism.

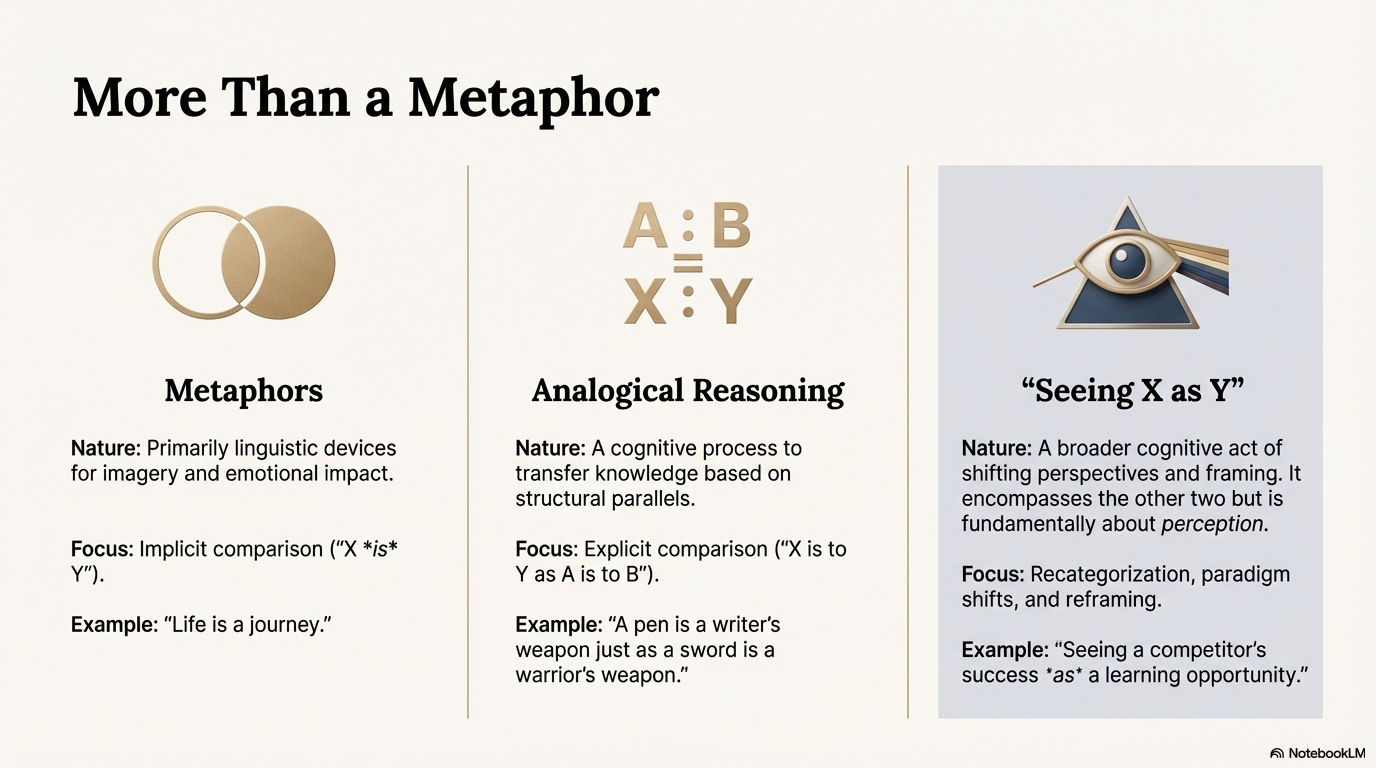

The operative word in such moments is not “is,” but “as.” We see one thing as another, and in that seeing, both are transformed.

This is the central claim of the “Spiked Virus” theory of cognition. It argues that ideas are not inert nodes waiting to be linked by a line. They are structured organisms. Like viruses, they possess surface features—”spikes”—that determine which other ideas they can bind to, infect, and ultimately reprogram.

Beyond “Connecting the Dots”

We are often told that creativity is simply “connecting the dots.” But dots are passive; they offer no resistance. You can draw a line between any two points and call it an insight.

Real ideas push back.

Consider the metaphor of the startup as a rocket—a favorite image in Silicon Valley. Both involve launches, require fuel, and aim for the sky. The connection feels inspiring until you attempt to solve a real problem, like team conflict or product-market fit. Rockets do not negotiate with mission control; startups must negotiate constantly. Rockets are engineered for autonomy; startups are social organisms. The analogy offers flavor but no function because the structural spikes do not align. The virus cannot find its receptor.

This line of thinking stems from a challenge posed by mathematician Stanisław Ulam to his colleague Gian-Carlo Rota. Ulam argued that artificial intelligence would remain merely “clever” until it could master the word “as.” To see a man in a car as a passenger, or a threat as an opportunity, is not a logical deduction—it is a perceptual reframing. The Spiked Virus theory takes up Ulam’s challenge by mapping the human mind not as a computer, but as an immune system navigating a dense ecosystem of viral ideas.

The Five Dimensions of Compatibility

For one idea to successfully “dock” with another, their spikes must align. The framework identifies five distinct classes of spikes:

Semantic Spikes: These carry the historical and definitional baggage of words. “Freedom” wears different spikes in a political speech (freedom from tyranny) than in a therapy session (freedom from neurosis).

Structural Spikes: These encode functional relationships. A city has arteries and a nervous system; a poem has meter and metaphor. If the structures don’t map, the analogy fails.

Emotional Spikes: These determine affective resonance. When Greta Thunberg declared “our house is on fire,” she did not provide new data; she switched the emotional spike from “analytic” to “urgent,” allowing the idea to replicate globally.

Ethical Spikes: These act as cognitive antibodies. The phrase “human capital” fits economic models perfectly but triggers immunological rejection in anyone whose ethical system centers on human dignity.

Temporal-Cultural Spikes: These ensure ideas fit their moment. “Democracy-as-majority-rule” docked successfully in the 18th century. In the age of digital misinformation and minority rights, however, the spikes collide, requiring a new conceptual shape.

When Ideas Click (and When They Crash)

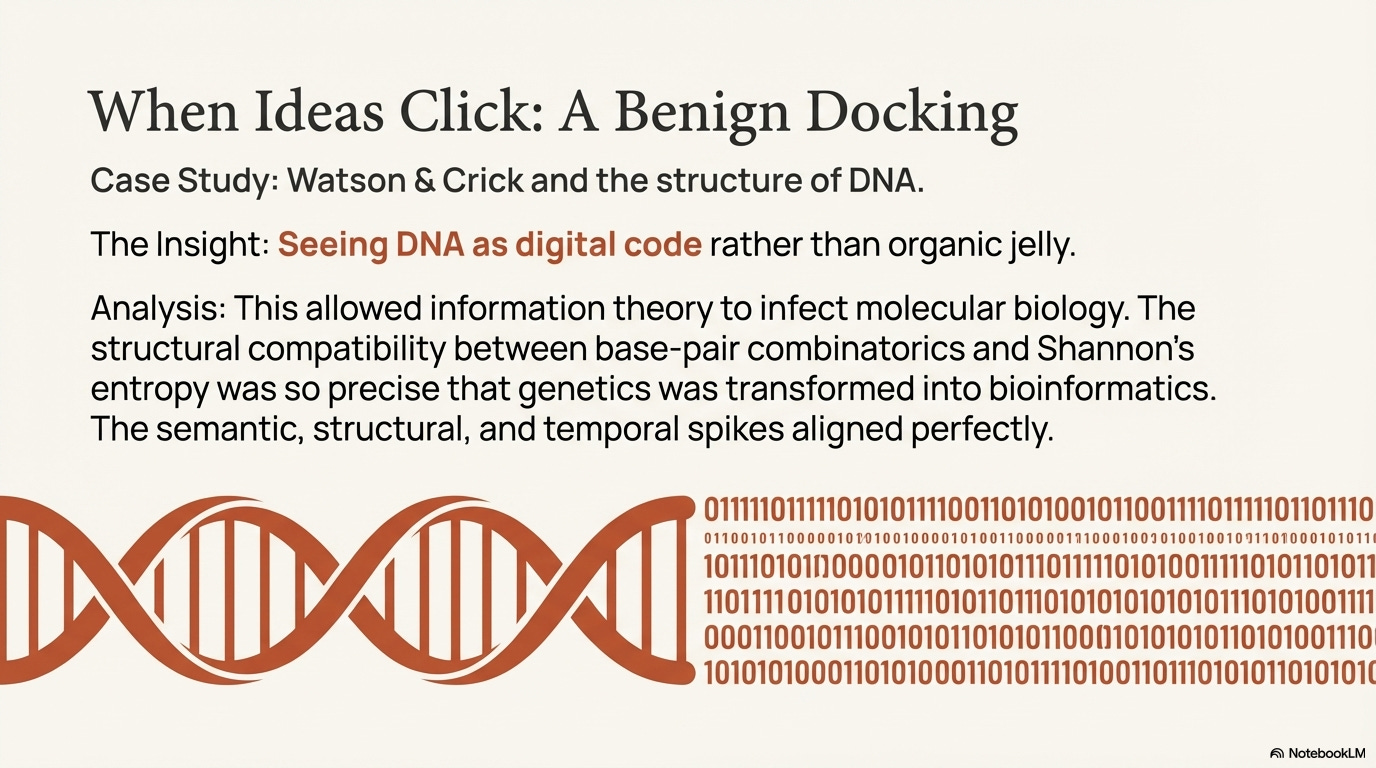

The power of this framework is visible in scientific revolutions. When Watson and Crick began seeing DNA as digital code rather than organic jelly, they allowed information theory to infect molecular biology. The structural compatibility between base-pair combinatorics and Shannon’s entropy was so precise that genetics became bioinformatics overnight.

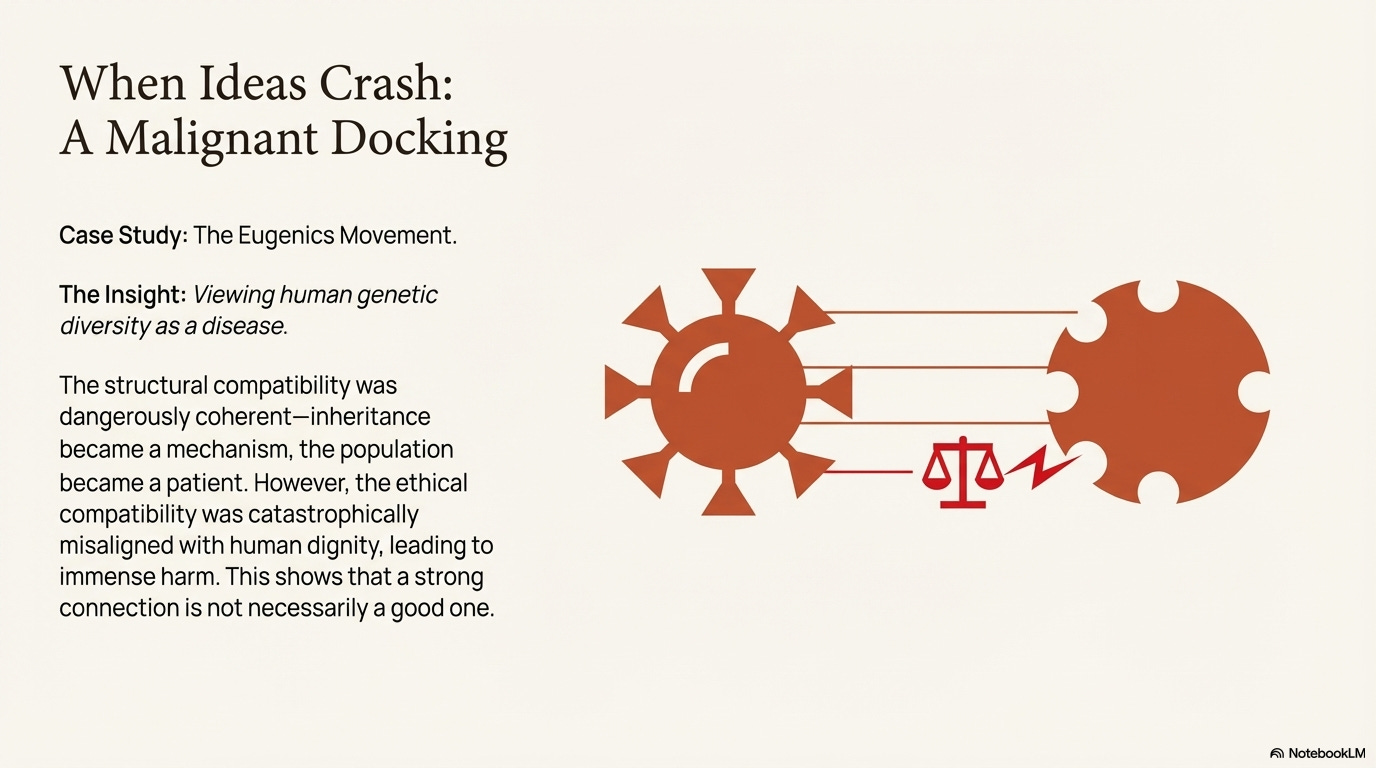

However, not all dockings are benign. The eugenics movement viewed human genetic diversity as disease. The structural compatibility was real—inheritance became mechanism, population became patient—but the ethical compatibility was catastrophically misaligned with human dignity.

Similarly, the “Sputnik moment” metaphor effectively drove Cold War innovation. Today, when applied to AI competition with China, it fails. The global economy and transnational science have changed the receptors. The idea still docks, but it produces empty rhetoric rather than meaningful action.

Spike Literacy: A Discipline of Attention

To navigate this ecosystem, we need “spike literacy”—the ability to evaluate which ideas deserve to dock with our thinking. This is mind-making: the practice of deciding which connections to host and which to reject.

Take the “attention economy,” a phrase that has infected our discourse. Its spikes are formidable:

Structural: Time is a finite resource.

Semantic: Attention is a commodity.

Emotional: Anxiety about distraction.

It has reprogrammed how we view human consciousness. But test its ethical spike: it turns mental life into a resource to be extracted. Test its edge cases: does deep, sustained love fit the model of an economy? The connection frays. Who benefits from this framing? Platform owners.

Spike literacy requires us to be the immunologist, not just the host. It asks:

Does this connection transfer practical value or just emotional flavor?

Where does the metaphor break down under scrutiny?

Can this idea adapt to changing circumstances?

The Pedagogical Paradox

How do we teach this literacy without killing creative spontaneity? We cannot teach people to generate insights, but we can teach them to analyze them.

The answer may lie in “vaccination”: exposing minds to weakened forms of misaligned ideas to build immunity. We can analyze how the “clash of civilizations” metaphor failed when confronted with global migration, or how “freshman” became “first-year student” as ethical spikes regarding gender evolved.

Ultimately, this returns us to Simone Weil—André’s sister and a philosopher in her own right—who wrote that attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity. To attend to the spikes of an idea is to give it the respect of critical appraisal. It is to refuse both blind acceptance and reflexive rejection.

The Spiked Virus is a generous metaphor because it does not distinguish between good and bad ideas at the level of operation; it only asks that you notice when you have been infected, and by what. It teaches you to be a good host: selective, vigilant, yet capable of the radical hospitality that allows a new idea to rewrite your world.

Key References:

Douglas Hofstadter, *Le Ton Beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language* (1997). The source of Ulam’s challenge and the original inspiration for exploring analogical cognition.

Stanisław Ulam, *Adventures of a Mathematician* (1976). Ulam’s original challenge to formalize the word “as” in artificial intelligence contexts.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, *Metaphors We Live By* (1980). The foundational text on conceptual metaphor, arguing that metaphor is not linguistic ornament but the structure of thought itself.