‘Everything in life is memory, save for the thin edge of the present’. — Michel Gazzaniga

This quote by Gazzaniga perfectly encapsulates the pervasiveness of memory in our lives, yet it also hints at its ephemeral nature.

Memory. The very word evokes a sense of solidity, of something carved in stone, a faithful record of the past. For centuries, this was the prevailing view – memory as a static repository of facts and experiences. Plato compared memory as impressions on a wax tablet, John Locke envisioned the mind as a blank slate upon which experiences etched their indelible marks, a library where each volume held a perfect, unchanging narrative.

But as our understanding of the brain and cognition deepened, this simplistic notion began to unravel, revealing a far more dynamic and nuanced reality.

Poets and storytellers, masters of the human experience, often depicted memory as fluid and malleable. Shakespeare, in his sonnet 30, lamented,

"When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste."

He recognized the poignant power of memory to reshape the past, coloring it with present emotions and desires.

Psychologists like William James further chipped away at the idea of a static memory store. In The Principles of Psychology (1890), he eloquently described consciousness as a continuous stream, an uninterrupted flow of thoughts and sensations. Memory, then, wasn't a collection of discrete, fixed records, but rather a dynamic process, constantly shaped by the ever-changing currents of our lives.

The idea of memory as a fixed, unchanging record was challenged by studies demonstrating how easily memories could be distorted, manipulated, and even implanted. Elizabeth Loftus, a leading memory researcher, conducted groundbreaking studies showing how subtle suggestions could alter witnesses' memories of events. Her work raised profound questions about the reliability of memory, particularly in legal settings.

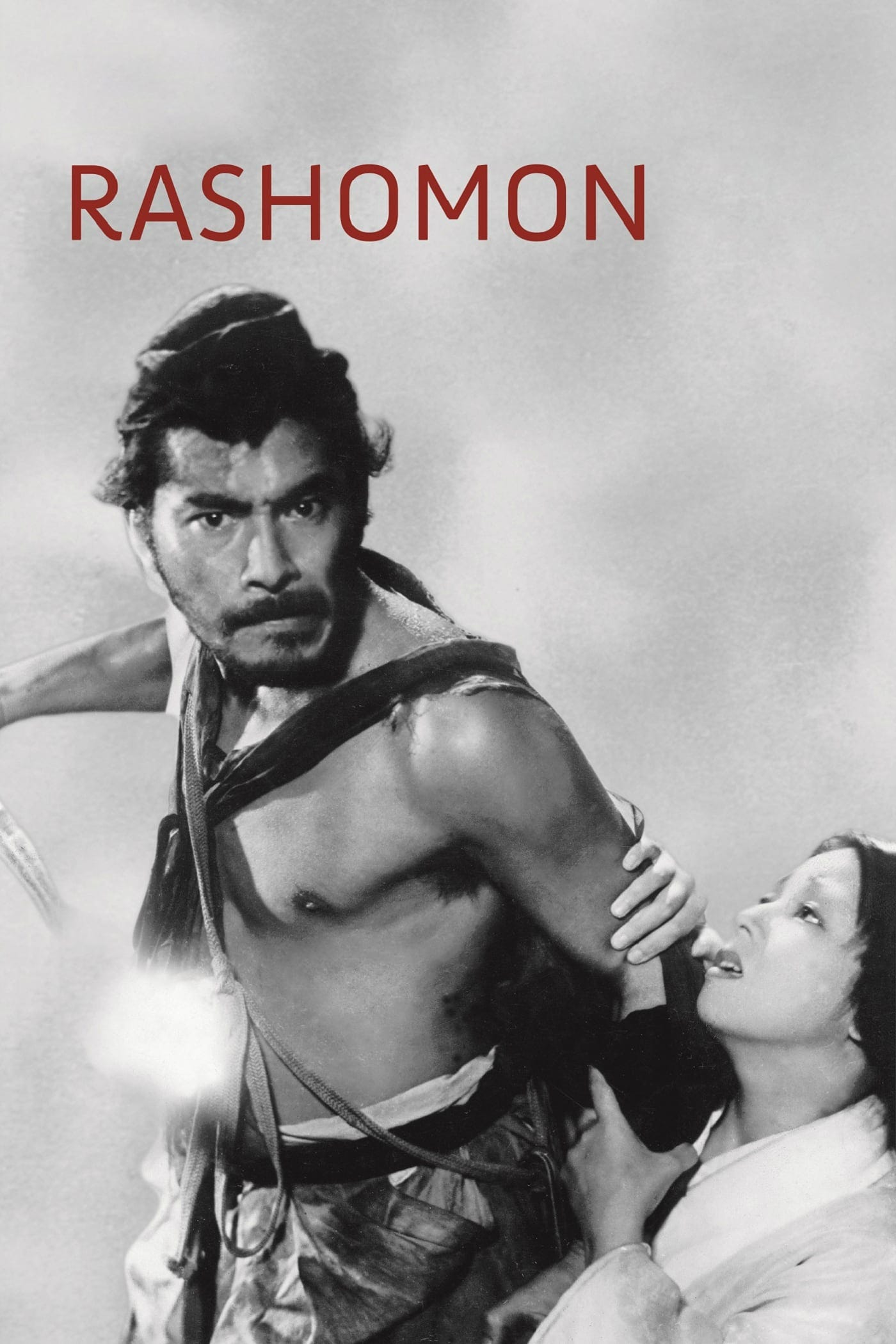

This dynamic nature is further illustrated by the "Rashomon Effect," named after Akira Kurosawa's groundbreaking film, perfectly illustrates this point. The film tells the story of a samurai's murder, recounted from the perspectives of four different witnesses. Each account differs significantly, not due to malice or deceit, but because each individual's perception is colored by their own unique experiences, biases, and self-interest. The "truth" of the event remains elusive, a mosaic of subjective realities.

But perhaps, this inherent "flaw" is, in fact, a strength. As the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead noted, “The present is alive with a sense of the past." Our brains did not evolve to be perfect recording devices, but rather to guide us through the complexities of a dynamic world. This demands flexibility, the ability to re-interpret, adapt, and learn from our experiences, rather than clinging to fixed, potentially outdated, representations of reality. Whitehead’s view of memory also emphasizes its creative aspect. By selectively integrating past experiences, organisms can generate novel responses to new situations.

Modern neuroscience has provided a biological basis for this understanding. Regions like the hippocampus and amygdala have been identified as crucial for memory formation and emotional processing. Yet, the biological mechanisms are far from simple. Pioneering thinkers like Heinz von Foerster, Gerald Edelman, and Michael Levin have proposed intriguing theories about the nature of memory that challenge traditional views.

Heinz von Foerster, in his explorations of cybernetics, argued that the function of memory wasn't simply to store data, but to make sense of the world, both past and future. He famously proposed that memory is a form of prediction that can be applied to the past as well as the future. Just as we use our knowledge and experiences to anticipate what might happen next, we also use them to reconstruct and make sense of what has already occurred. We are constantly seeking patterns, making connections, and filling in the gaps, constructing coherent narratives that help us navigate the world.

Gerald Edelman, a Nobel laureate neuroscientist, provided a biological basis for this idea with his "Theory of Neuronal Group Selection." Edelman proposed that memory isn't about retrieving fixed engrams, but rather a process of recategorization. Every time we recall a memory, we are essentially re-experiencing it through the lens of our current neuronal network, which has been shaped by subsequent experiences. This means that every act of remembering is also an act of modification, subtly altering the way that memory is stored and retrieved in the future.

“If our view of memory is correct, in higher organisms every act of perception is, to some degree, an act of creation, and every act of memory is, to some degree, an act of imagination “ - Gerald Edelman, Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist

Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at the forefront of bioelectricity research, takes this idea even further. He views memory not just as a property of brains, but as a fundamental aspect of all living systems, operating across scales from single cells to entire organisms. Levin proposes that memories are essentially messages from past selves, encoded not just in synaptic connections, but in the very structure and dynamics of our bodies. These messages are constantly being reinterpreted and re-mapped as the organism grows, develops, and adapts to new environments.

The crucial point is that we tend to remember information that is most salient and beneficial to us.

Metamorphosis, regeneration, and even the everyday turnover of cells are all examples of this dynamic memory process at work, ensuring the continuity of the self across radical transformations.

Imagine, for example, a caterpillar metamorphosing into a butterfly. While the physical structure of the organism undergoes a dramatic transformation, certain memories persist, allowing the butterfly to navigate its new world and seek out food sources. These memories, however, are not simply stored data, but rather prompts that trigger specific behaviors in response to cues in the environment. The meaning of those memories has been reinterpreted and re-mapped onto a completely new body plan.

This dynamic view of memory has profound implications. It explains why eyewitness testimonies can be unreliable, how trauma can reshape our memories, and why even cherished childhood recollections can be a blend of fact and fiction.

The movie "Total Recall" (2012) takes this concept to a thrilling, if unsettling, extreme. The protagonist, plagued by disturbing dreams, undergoes a procedure to implant false memories of a thrilling adventure on Mars. As the lines between reality and fiction blur, he is forced to confront the question: who is he, if his memories are not his own? "Total Recall” highlights the power of memory manipulation and questions the very essence of identity. If our memories can be altered, what does it mean to be "us"?

This inherent malleability necessitates a cautious approach towards our own memories. We must acknowledge their subjectivity, their potential for distortion, and their power to shape our present and future.

Confabulation, the unintentional fabrication of false memories, can arise from the brain's innate drive to create coherent narratives. This drive, while essential for sense-making, can lead us astray, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. Unresolved trauma, for instance, can lead to fragmented memories that are unconsciously reshaped to protect the self, leading to distorted recollections that can have devastating consequences.

"Confabulation is a kind of cognitive plasticity that emphasizes the present, the future, and the gestalt over the literal past – it occurs when a mind actively modifies and fits its beliefs to a current context, altering and reinterpreting memory data as needed..." — Michael Levin, "Self-Improvising Memory"

Similarly, the very process of reinterpretation, so crucial for adapting to new circumstances, can become a source of confusion and even self-deception. Past memories, if not carefully examined and re-contextualized, can lead to misinterpretations of present situations, perpetuating unhelpful patterns of thought and behavior. By acknowledging its fallibility, its dynamism, and its remarkable capacity for meaning-making, we can better navigate the complex terrain of our own personal histories, and perhaps even find a path towards greater wisdom and self-understanding.

The concept of constructive memory not only enhances our understanding but also has implications for treating memory disorders such as Alzheimer's disease. Instead of concentrating solely on preserving existing memories, we could investigate new therapeutic strategies that highlight memory's adaptive, constructive aspects. This approach involves finding methods to assist patients in forming new, meaningful connections and narratives as previous ones diminish.

By recognizing memory as an active process of re-creation, we can become more critical consumers of our own past, questioning our assumptions and biases. This critical engagement with our own narratives can lead to greater self-awareness, empathy, and ultimately, a richer, more meaningful understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Ultimately, the enigma of memory persists. We continue to decode the elaborate interplay of biological and cognitive processes that intertwine our experiences into the elaborate and multifaceted stories of our lives. Memory is not a passive record, but an active force, shaping our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.